World Hepatitis Day (28 July) is an annual global public health day that aims to raise awareness of viral hepatitis. This year, the theme is “It’s Time for Action”, highlighting the need to encourage individuals, partners and the public to work together towards the World Health Organization’s (WHO) global strategy: eliminate hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030.

Professor Greg Dore, who leads the Viral Hepatitis Clinical Research Program, highlighted the timeliness of the theme and the crucial work ahead. "With less than seven years to achieve the WHO viral hepatitis elimination targets, and some momentum lost in recent years, the next few years are absolutely crucial to enhance prevention, linkage to care and treatment for hepatitis B and C,” he says. “Australia has been an international leader in providing equitable access to effective interventions for viral hepatitis and the Kirby Institute continues to enhance understanding of strategic solutions required and facilitate effective intervention implementation through innovative research."

In response to World Hepatitis Day, we shine a spotlight on the disease, its prevalence and just some of the current research projects happening at the Kirby Institute in the field of viral hepatitis.

What is hepatitis and how much of a concern is it?

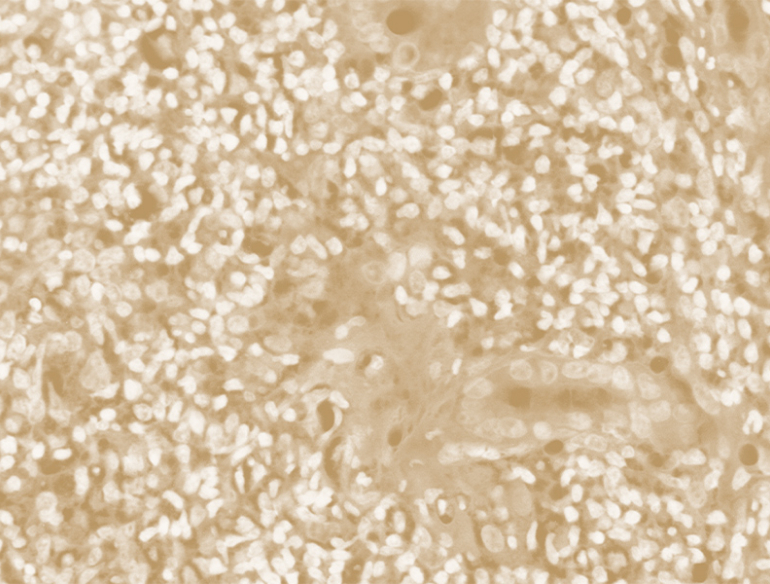

Hepatitis is an infection of the liver that causes inflammation and damage. Left untreated, it can lead to a range of health concerns, some of which can be fatal, including liver failure and liver cancer. While there are several strains of viral hepatitis, types B (HBV) and C (HCV) cause chronic infection and are two of the most prevalent types worldwide.

Viral hepatitis is a growing health concern globally, with WHO citing it as the second leading infectious cause of death globally. In its 2024 Global Hepatitis Report, WHO states around 1.3 million deaths per year can be attributed to viral hepatitis – the same as tuberculosis – and the number of lives lost is on the rise.

Data from the report, gathered from 187 countries, showed that from the estimated number of deaths each year, 83 percent were caused by hepatitis B, and 17 percent by hepatitis C. Shockingly, there are 3500 people dying each day globally due to viral hepatitis infections.

In Australia, while there is still some way to go, there is good news. According to the Kirby Institute’s Annual Surveillance Report 2023, new hepatitis B and hepatitis C diagnoses have declined since 2013 and 2016, respectively. The availability of highly curative direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C has turned around the rising burden of liver failure, liver cancer, and liver-related deaths. But many people still develop serious liver disease without diagnosis – a major "missed opportunity" for effective interventions.

Here at the Kirby Institute, we undertake world-class epidemiological, clinical and laboratory research that improves outcomes for people living with viral hepatitis. Here is a brief overview of some of the work we are doing in close partnership with the communities impacted by hepatitis.

Creating a first-of-its-kind database with the REACH-B Study

The REACH-B Study, or REal-World Assessment of People Living with Chronic Hepatitis B in Australia, is a national observational cohort study currently being undertaken by the Kirby Institute in collaboration with health services and clinics across the country.

It aims to gather health data on people with chronic hepatitis B infection in Australia and, as a result, use that information to help improve health outcomes, resources and levels of care. That’s because only 70 percent of Australians living with chronic hepatitis B have been diagnosed and just 13 percent are receiving treatment – well below the government’s National Hepatitis B Strategy target of 20 percent by 2022. The study aims to change that.

“We don’t actually know the exact number of people who are eligible for treatment, because a national database to track chronic hepatitis B information doesn’t exist,” says Senior Project Officer Jessica Carter. “By gathering demographic, clinical care, treatment and laboratory data from medical records, we’re able to paint a real-world picture of the disease and the people it impacts.”

REACH-B is a major study, collecting data from up to 10,000 people living with chronic hepatitis B through health services every six to 12 months for at least five years.

“REACH-B is an important Australia-wide study aimed at better understanding the hepatitis B treatment landscape,” explains Principal Investigator, Professor Gail Matthews. “This data will be crucial to understanding the chronic hepatitis B stages of care, identify the areas and populations where targeted interventions are required to improve health outcomes, and to assess progress towards the elimination of hepatitis B as a major public health threat.”

A world-first scale-up of testing for hepatitis C

Research is facilitating progress toward hepatitis C elimination, too, thanks to progress of the National Australian Hepatitis C Point-of-Care Testing Program, led by the Kirby Institute and the International Centre for Point-of-Care Testing at Flinders University.

Point-of-care testing for hepatitis C infection can help test, diagnose and initiate treatment within a single, one-hour clinic visit. Following successful trials and a subsequent scale-up of services nationwide, it is shown to be an effective way of delivering highly accurate, swift, judgement-free and relatively mobile testing, enabling people to know their status and commence treatment if needed.

Professor Jason Grebely leads a team of researchers who are working in close partnership with services across Australia including drug treatment clinics, needle and syringe programs, community health centres, mental health clinics, mobile outreach models, homelessness services, Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisations and prisons to scale up point-of-care testing for those at risk of hepatitis C. “In the first two-and-a-half years of the program, we performed more than 29,000 hepatitis C tests, diagnosed more than 3,000 people and treated more than 1,600 people, which is having a huge impact on the health of these individuals and their communities,” he says.

“Hepatitis C elimination in Australia is entirely possible, and we know that point-of-care testing is one of the best ways to facilitate getting people tested, treated and cured. Ultimately, we want to optimise point-of-care testing delivery in a range of settings and sustain the program into the future, to ensure those at risk are able to access it and get onto life-saving treatment if needed.”

Gathering vital data to shape hepatitis healthcare

Population-level data is crucial in gathering information about infectious diseases, and hepatitis is no exception. Data linkage is a process of bringing together multiple data sources from different sources such as disease notifications, hospitalisations, death records and medical billing data to create richer data sets, from which researchers can monitor trends and uncover gaps and barriers in the health system.

The Kirby Institute’s NSW viral hepatitis data linkage project, which launched around 2006, is an ongoing project that links information from all hepatitis B and hepatitis C notifications in New South Wales over an almost 30-year period from the early 90s through to today. From this dataset, researchers can monitor the trends in hepatitis infections over time, disease outcomes, testing and treatment uptake and demographics – essential information when designing targeted testing and treatment strategies.

“Our data linkage study shows us that, since WHO’s call for viral hepatitis elimination, morbidity and mortality due to hepatitis B and C liver failure and liver cancer have been declining compared to pre-elimination trends, which is a huge positive,” says Senior Research Associate Dr Heather Valerio, who works on the project. “Data linkage has also helped uncover population groups that continue to face barriers to care so that interventions in these groups can be increased, such as migrant populations or people who inject drugs.”